We must admit, we did not know much about Bolivia. Some general knowledge and bits and pieces from the news. We had put a a couple of markers on a map of things we wanted to see and we had read up on some of these spots. That was it, roughly. And that is why Bolivia hit us with full force, like no other country on our entire trip.

Bolivia only gained its independence in 1825 through the military action of Mr Sucre who acted on behalf of Simón Bolivar. The first war took place in 1836 against Chile and Argentina. It ended in defeat. In 1879 the second war took place, the so-called War of the Pacific or Salpeter War. Bolivia was defeated once again, this time by Chile. And it lost its access to the Pacific. This remains a huge topic in the country. In 1932 the Chaco War took place when large parts of Bolivia were lost to Paraguay. And guess what? This war equally ended in defeat.

Everything that followed was not that great: Economic decline, social unrest, protests, military coups, interests of foreign powers and some democracy. All of it took place up into the 21st century. Finally, in 2005, the coca farmer Evo Morales showed up and was elected president. The first indigenous president who lived up to his promise to nationalise the natural gas industry in May 2006. That’s when the “Sommermaerchen” took place in Germany. Just to provide some context.

In 2009 Bolivia got a new constitution, with a particular focus on the rights and the culture of the indigenous populations. The constitution als set forth that a president may only be re-elected once. As Morales started his second term when the new constitution was introduced, nobody was really surprised that there was some protest when he ran for election for a third time in 2014 and was re-elected. That much for a maximum of two terms.

Elections are taking place this year again. And guess who is running again. Mister Morales. Who cares about what the constitution says? But as you cannot just ignore the constitution, he decided to hold a referendum to allow him to run for a fourth time. Unfortunately, the referendum did not have the desired outcome. Mr Morales was not allowed to run. But where there is corruption, there is a way. Last December the supreme court of Bolivia ruled that no public office in the country may be limited in term. Evo may now run for president for the rest of his life. I don’t think that this is what Mister Bolivar had in mind. No matter whether Mister Morales will be re-elected, the protests in the country are becoming more and more audible and we believe the bottom line is that the population has had enough of Evo and his dealings.

It does not seem too surprising that Bolivia is a tough place. My short summary of the history of the country clearly over-simplifies matters, however we had the impression that the majority of the country does not participate in the achievements and the wealth of the country which clearly does exist. Large parts of the rural population live in the same way they did hundreds of years ago. Infrastructure is distributed randomly.

After leaving the Salar de Uyuni behind, we traveled to Sucre. En route, we wanted to go and see a further train cemetery where the last train that Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid had robbed has found its resting place. The navigator tried hard to find out which of the wrecks was supposed to be “the train” and we are pretty confident that we took shots of the right one.

We carried on to Sucre. The landscape up to Potosí was rough and inaccessible. The altitude kept eating at us and we continued rocking and rolling through Bolivia at 13,000 feet. We just wanted to arrive and relax – anywhere. But first we needed to go through Potosí. Potosí at some point was the wealthiest city in South America because of the silver mine close by which has the largest silver deposits of the world. Therefore Potosí was already wildly popular in the 16th century and had more than 200,000 inhabitants back then. As for most mining towns, they are not really that charming. Potosí is a dusty and dirty dump. As we had no inclination whatsoever to see more of Potosí, we just drove through and were glad once we left the town behind.

After Potosí however the landscape suddenly turned more beautiful, the sun came out on this rainy day and our mood improved instantly. We noticed that Bolivia is way more populated than the other places we traveled through. One village after the other. Even on that “side road” that we picked for our lunch break, i.e. the mudhole in the middle of nowhere, several people drove and walked past us, some offering a couple of words of conversation. At this point we noticed something else. Nobody smiles in this country. Literally nobody. More to follow on that.

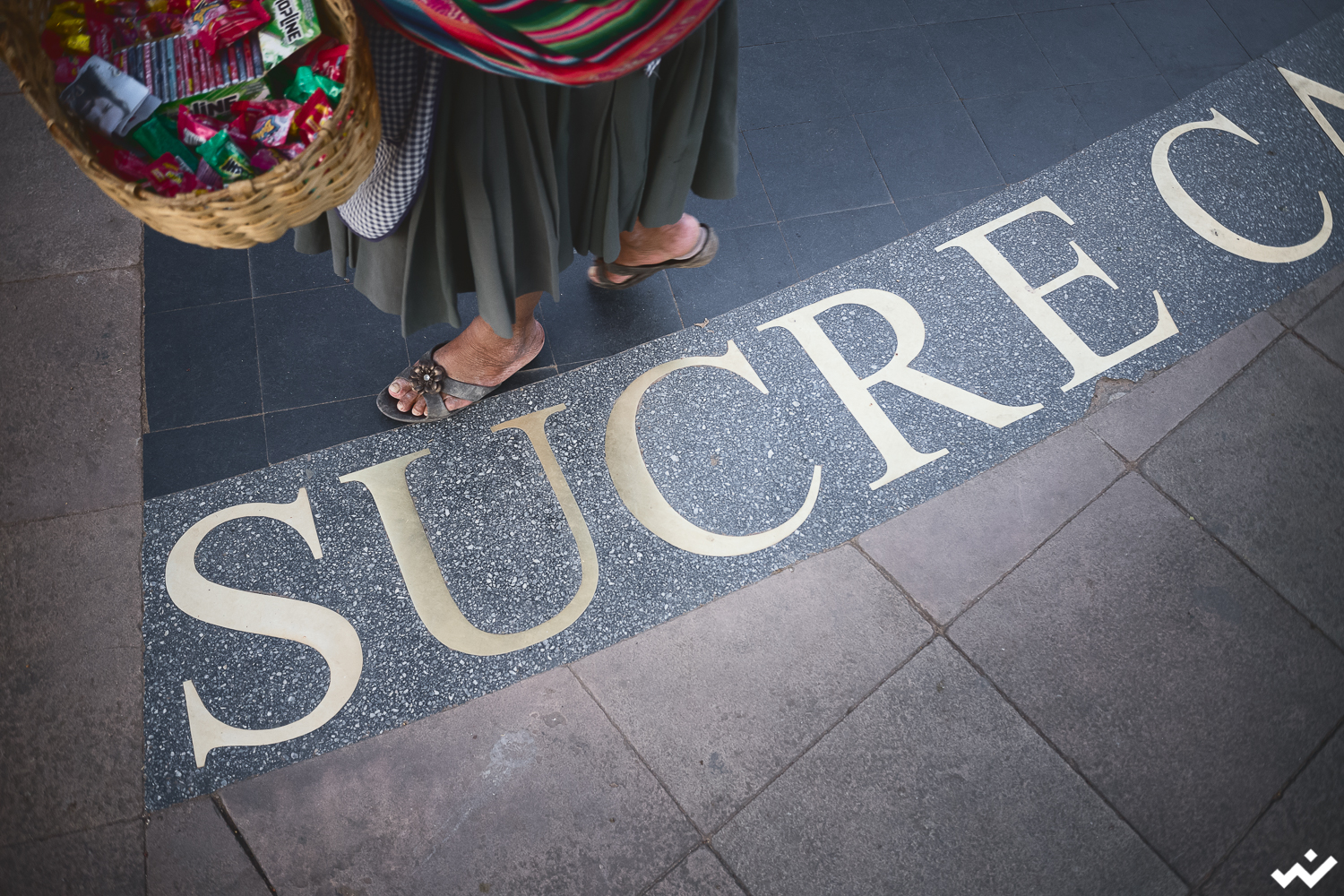

After 400 km, we finally arrived in Sucre and were lucky enough that we had the well-known campsite for overlanders in the middle of town all to ourselves. Having spent a long time in nature without any city life, we jumped right into it. Sucre is a charming and pretty town with many colonial buildings, loads of cafés, restaurants, markets and all that makes city life interesting and fun. We loved it and I even got carrots thrown at me.

In Sucre we picked exactly that one day to visit the city museum when the museum was shut because of a parade. The parade was about the constitution, the lost salpeter war and that they would get all that was lost and that they were entitled to back one day. Quite obvious, right?

After a couple of days of R&R in Sucre, good food and some culture, we carried on northwards. On our last evening in Sucre we met a Swiss couple on our campsite again who we had already met in Patagonia several times. That’s how these things go. You keep running into each other.

En route to Cochabamba, shortly after Sucre, lies Cal Orcko. A paleontological site where hundreds of dinosaur tracks of at least 294 different dinosaurs can be seen. After we drove past the entrance at first, we found the place in something that looked like a mix between a truck stop and a quarry. As always, we were early. As it was the weekend, the park only opened at 10 am. We therefore had to wait for half an hour. We confirmed with the guard that there was a guided tour to the tracks after the park was opened and decided to wait. We then bought our tickets, entered and asked for the meeting spot for the tour, only to be told that the tour started at noon but that we could spend time visiting the rest of the park until then. What you need to know is that the rest of the park is for kids. Real-size plastic figures of dinosaurs and so on. We thought deep and hard about whether we wanted to wait for another two hours to see a couple of imprints on rocks. As you probably know, we don’t like waiting and we don’t like groups, so we cut this pointless little excursion short and carried on. Museums in Bolivia and we were just not meant to be it seems.

Our further trip from Sucre via Cochabamba to la Paz was pretty unspectacular. We traveled through beautiful landscapes every now and then which resembled one or the other part of Europe. We drove uphill and downhill, in the midst of convoys of trucks which were traveling between the large number of mines. Tons of construction sites in the middle of nowhere in the mountains. This probably is a good time to tell you more about traffic in Bolivia.

Or rather about the other traffic participants in Bolivia. Whoever believes that German drivers are reckless and the traffic in Southern Italy is unbearably chaotic, should get in a car and take a drive around Bolivia. After that driving anywhere in Europe is a relaxing affair. Driving considerately is an unknown concept in Bolivia. Egotism rules, everyone just drives, no matter what’s happening around them. Leave it to the others to brake. Public transportation consists of minivans running group taxi services. There are millions of these, at least it feels like it, and they all stop on literally every street corner, just pulling over, blocking the road or pulling out of that road block randomly. Throw in some cyclists, tuctucs and some trucks moving at random speed (probably depending on how many decades it has been on the road already). And all of this takes place on a mix of brandnew tar and mud, again randomly distributed. The main tar road may just change to a mud track without any notice and we as spoilt Europeans may need a moment to adjust.

And then there is La Paz. La Paz already is at quite an altitude. But the altitude differences within the city are amazing. The wealthy parts of the city are at 10,500 feet while the poorer part of town, El Alto is at 13,000. Traveling through the city takes you up and down as it is a former canyon. Imagine all of this while sitting in Humphrey, weighing roughly three tons, and with nothing happening in the lower rev ranges because of the altitude. He only gets going once the turbo kicks in. As you’d expect, the other traffic participants were glued to our backside and started honking frantically if we did not move instantly at the pace they thought was appropriate. It felt a bit like driving school – “practising a hill start”. To make matters worse, our Garmin inexplicably decided to stop working in La Paz. We were lucky enough to find an online trader who sold us an earlier version of the device – selling it out of his apartment. Unfortunately though, this one gave up on us a day later. With the same data set put onto it.

After all the exertions in South America so far, Humphrey deserved and got new brake pads before we left for Peru the next day. We decided to take a detour to Tiwanaku before crossing the border. That’s one of the most important historic sites in Bolivia. We had to drive all the way through El Alto, the poorer quarter of La Paz, and guess what, it was a total traffic nightmare. Finally, when we could leave La Paz behind and start picking up some speed, we were stopped for speeding. After a ten minute negotiation with the police officer in Spanish we were able to convince him that we would happily pay ten Dollars if we could carry on without further bureaucracy.

Tiwanaku. Assuming it is one of the most important archeological sites of the country of one of the most important advanced civilisations of the country, you’d expect… well, but that’s exactly the point. The site was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 2000 but even the UNESCO wanted to withdraw the status as the people locally did not manage or invest any money to properly protect the site and people were just trampling all over. It really is a shame. It must have been an amazing and powerful city historically, it’s evident even from the existing remains. But there is no love, respect or appreciation for it.

To round off our experience, we visited the local museum with its lovingly designed courtyard. We did not let any of this affect our mood though as we were still really glad that we were able to bribe the police and did not need to return to the police station in El Alto.

We carried on via further mud tracks where the map said there should be a proper road, past construction workers asking us for booze until we finally reached Lake Titicaca after several further kilometers. We crossed to Peru via a small wooden boat as things are done here.

Bolivia surely did not become one of our favorite places and we struggled a bit with the country as you have probably sensed. One of the key reasons surely is that nobody, really nobody, ever smiled back. We really made an effort, even more than we normally would as we really did not get it. Even the kids who normally always smile at you – no matter where in this world – did not smile back in Bolivia. And it just does not make you feel welcome. On the other hand Bolivia was the country we visited that was least conformist, it was rough and authentic. A place for adventures. And that’s what we experienced in Bolivia: an adventure.